“I didn’t finish my degree because I got involved with student protests and I was chased away.”

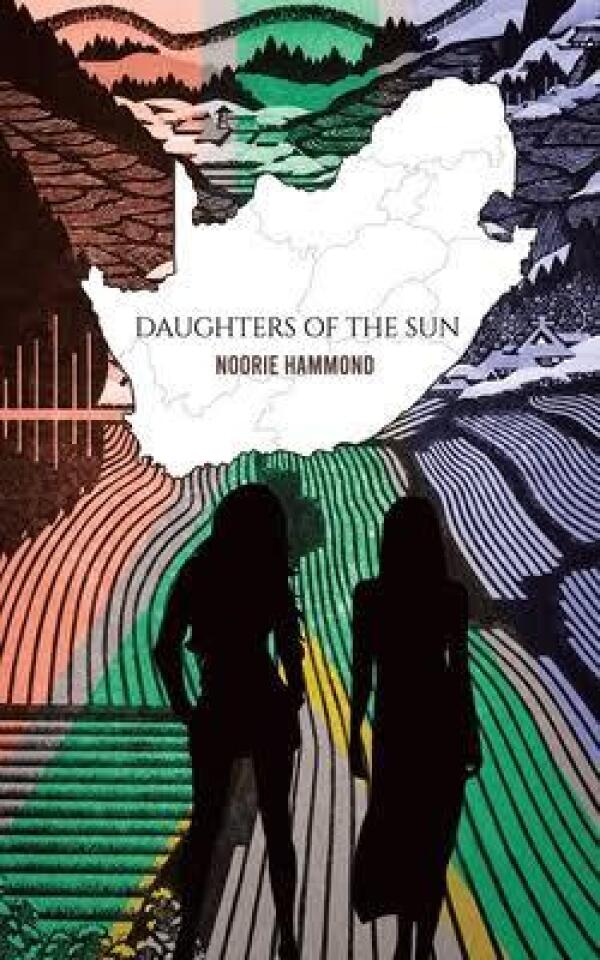

A FORMER Kimberley woman, who was forced to leave her hometown and country after she fell in love with a white Afrikaner, has recently had her book, Daughters of the Sun, published.

The write-up for Noorie Hammond’s book describes how the reader will “walk hand in hand with the strong characters from the beginning of the story of a typical South African family of Indian lineage as they live with the oppression of the apartheid era in South Africa that lasted over forty years”.

“The compelling story is based on true occurrences which affected the lives of ordinary people and how they dealt with it amidst sacrifices and hardship, love and happiness, comedy and tragedy from the early days, starting with the indentured Indian labour system in South Africa until the new democratic dispensation in 1994 in South Africa.”

Speaking from her home in East London, where she moved after her husband, Steven Hammond, died four years ago, Hammond yesterday related her early years in Kimberley, where she was born, went to school and matriculated at William Pescod High School.

“My parents were born in South Africa but their parents were from India,” Hammond explains.

After completing her matric, Hammond went to study law at the then Salisbury Island University, off the coast of Durban, which was earmarked for Indians. “I didn’t finish my degree because I got involved with student protests and I was chased away.”

She came back to Kimberley, where she met and fell in love with her husband-to-be.

“He was a white Afrikaner – but love doesn’t look at colour. As our relationship became more serious, we came objects of interest to the security police and were constantly harassed. Everything we had to do undercover because our relationship was a transgression of the Immorality Act and the punishment was a three-month jail sentence. However, even after one came out of jail, you never knew what would happen to you as people just disappeared.”

She describes how her family, fearing for her safety, urged the young couple to break up. “We tried several times but each time we got back together and eventually we realised that we would have to leave our country of birth.”

Hammond describes this as one of the most difficult decisions of her life. “I was born in South Africa, so were my parents, my people were there. That is who I was. Although I was of Indian origin, I couldn’t leave and go to that country – I couldn’t even speak the language. It was very sad to leave because this was my family.”

Settling

The couple moved around, first going to the Transkei, and then to Maseru in Lesotho, before finally settling in Mafikeng in then Bophuthatswana. “We stayed for most of our lives in Mafikeng and I only moved to East London after my husband died.”

While she never completed her law degree at Salisbury Island University, Hammond studied through Unisa, majoring in Psychology and Literature.

“My first attempt at writing was a small book of poems that was published while I was still a young woman living in Kimberley. The book was on display at CNA and I remember we used to go and look at it through the window and I was so proud.

“However, it was removed from the shelves by the security police, who also visited our house, looking for additional copies.”

Hammond remembers her mother burning all the copies the family had of her collections of poems. “Today I don’t have any copies of it – I am not sure whether it is still available.”

She also wrote another book, which she describes as memoirs, when her husband died. “I was so depressed after his death that I locked myself in the bedroom and wrote the essays for three months.”

She describes Daughters of the Sun as “historical fiction”. “I changed the names of the people involved but it is based on true circumstances.”

“I wanted to write the book because I wanted to show what ordinary people went through to survive during the apartheid years in South Africa and how it affected their daily lives. There are lots of books that have been written about apartheid but these are about people in the Struggle who went on to become icons – not just the ordinary masses, who had to adapt their circumstances just to survive.”

With yesterday marking the 30th anniversary of the release of Nelson Mandela from Victor Verster Prison, Hammond remembers watching the historic moment as he walked out of the prison’s gate hand-in-hand with Winnie, on television in Bophuthatswana.

“This was a difficult time in Bophuthatswana because the former homeland was incorporated back into South Africa, but the president, Lucas Mangope, refused.

However, when it was time to cast her vote, Hammond joined the long queues of excited people to make their first cross.

One of her treasured possessions today is a copy of a DFA poster, dated October 16, 1980, with the bold letters: “Colour-bar lovers flee Kimberley.”

The article in the newspaper relates how “Miss Noorie Cassim, an Indian woman, and her white boyfriend left Kimberley to settle in the Transkei”.

Cassim, at the time, was a perforator operator at the DFA’s type-setting department while her boyfriend was a panel beater.

“Miss Cassim’s father, city barber Mr Mohammed ‘Koki’ Cassim said the couple arrived safely in the Transkei, so ending two years of constantly having to look over their shoulders to see who was following them.

“In the two years, they many times changed cars if they thought they were being followed,” her father told the DFA reporter. “We were always afraid of the law.”

Mr Cassim, a staunch Muslim, said he saw nothing wrong with his daughter’s relationship across the colour line. “What’s the difference?” he was quoted as saying.

Mr Cassim had only praise for his daughter – the baby of the family – who had been the main source of income to the family for a number of years. “Before they left, I gave them my blessing.”

For Hammond, her story will now never be forgotten.