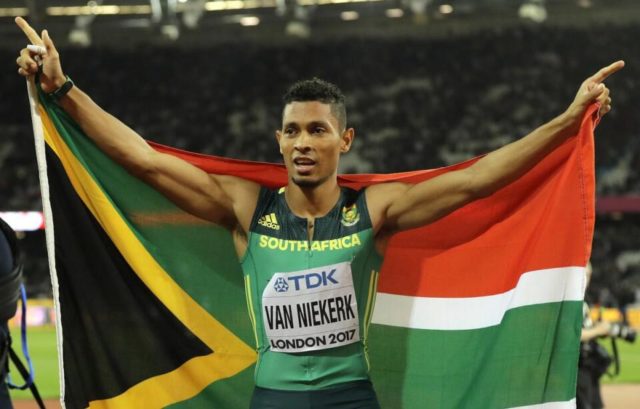

Doubt is part of the process for South Africa’s golden boy Wayde van Niekerk

South Africa’s 400m world record holder Wayde van Niekerk’s return from injury to competition in mid-February was filled with nerves and trepidation.

In an unofficial 100m race on grass it have been a formality. A routine rust-buster. A glorified training session. Yet for the 27-year-old South African, it felt like so much more.

When the gun fired that evening in Bloemfontein, he ripped up the home straight and took victory in a hand-timed 10.20. It meant nothing, yet it meant everything.

For the past two years, this simple act of sprinting had been filled with so much doubt. But here, at last, was some certainty, proof that his body could once again be taken to full throttle.

“There were definitely a bit of nerves, questions,” he told worldathletics.org. “But I decided to put all those aside and see what my body wants to do.”

Later that week, Van Niekerk rocked up to another local meeting in Bloemfontein and, on a synthetic track, clocked 20.31 for 200m and 10.10 for 100m in the space of an hour.

“It showed me I still have that speed and I definitely still have the strength that I had before the injury,” he says. “That gave me a massive boost.”

Then injury struck. The one that divides his career down the middle: before and after October 2017.

At the time he was the reigning Olympic and world champion, but his decision to take part in a charity touch rugby match soon brought his career to a standstill. Van Niekerk sustained medial and lateral tears in his meniscus and tore his anterior cruciate ligament (ACL).

Amid the punishing physical pain that followed and the long, lonely hours of rehab, perhaps the hardest thing to deal with was the guilt. Van Niekerk carried it like a loaded barbell.

“I can’t blame anyone else for my injury,” he says. “I’m the one who made the decision to play a rugby game, the one who put myself in that position. I’m a professional athlete and the decision I take is on me but what that (brought was) a bit of guilt and wishing I did not do what I did.

“But it was my reality, it happened and putting blame on it wasn’t going to get me to come back stronger.”

“Doubt is part of the process,” he says. “There were doubts even before I was injured. I’m a very critical person of myself and I’m very hard on myself so that creates some doubt and questions.”

Severe injury can thrust athletes through the various stages of grief, lamenting the loss of their health, longing for its return. They can experience denial, anger, depression, but it didn’t take long for Van Niekerk to reach the final stage: acceptance.

“Knowing myself and spending time with my mentors, it made it easier to snap out of the dark places when the negatives were creeping up on me,” he says. “It helped me seek a positive or a peace within this chaos.

“Mentally I’ve been practising to get myself more confident so when things aren’t going my way, I stand firm in who I am and what I believe in. That’s what’s driven me forward. Knowing my quality and what I can achieve has made it so much easier to work harder than ever before to come back.”

The key is building fitness, brick by brick, back to where he wants it to be.

“I feel I have the strength and speed to produce world-class times and challenge my record,” he says. “That’s where my mind is set.”

Van Niekerk remains the only man in history to run under 10 seconds for 100m (9.94), 20 seconds for 200m (19.84), 31 seconds for 300m (30.81) and 44 seconds for 400m (43.03), but it’s that latter mark that remains the apple of his eye.

Is 42-point the next target?

“It’s got to be,” he says. “I’m someone that’s stuck on going sub-43 and with that I want to improve my 100m and 200m times. I believe I’ve got the abilities to be competitive internationally in all three events.”

Like most of the world, life for Van Niekerk has not been normal for quite some time. South Africa imposed one of the world’s strictest lockdowns in late March, which kept him confined to training at home for more than a month.

“Luckily I have a gym set up at home,” he says. “I’ve got quite a technically advanced treadmill so it challenges me in ways that become quite difficult.”

The journey to getting fast will be taken slow, but Van Niekerk is still relishing a return to racing once it’s safe to do so.

“Obviously we need to wait patiently, but when the opportunity comes we need to take it. We need those races to get fit, but you have to choose wisely because you don’t want to hurt yourself and sit out for another three years.”

The injury, says Van Niekerk, has forced him to “step up the game even more intense than before”.

“I need to focus on me and where I want to be as an athlete and what I want to achieve: that’s to continue to be number one and improve myself, strengthen myself,” he says. “Whoever pops up during this process, I’ll accept the challenge.

“May the best man win.”

African News Agency (ANA)