OPINION: Having five hung metros does not augur well. Service delivery will suffer. Coalitions are not sustainable. The ones that will be formed have been imposed by the election results, they were not planned, writes Professor Bheki Mngomezulu.

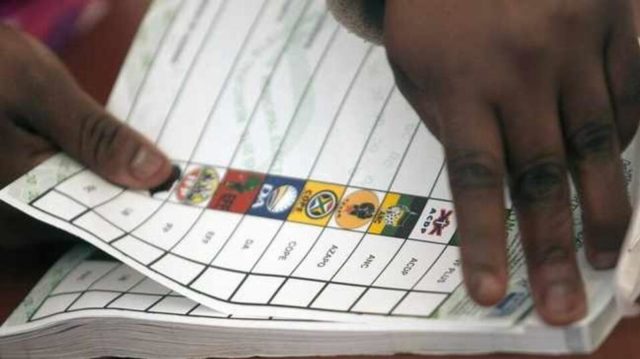

AS THE 2021 local government elections (LGE) approached, all the big political parties had their eyes fixated on South Africa’s eight metropolitan municipalities: Buffalo City, Cape Town, Ekurhuleni, eThekwini, Johannesburg, Mangaung, Nelson Mandela Bay and Tshwane.

The assumption was that the fate of Buffalo City, eThekwini, Mangaung and Cape Town was already known. It was anticipated that the first three would go to the ANC while Cape Town would go to the DA.

Given what happened in 2016 when the ANC performed better than the other political parties but needed the support of the African Independent Congress (AIC) to run Ekurhuleni, there was no certainty that the ANC would win this metro with an outright majority.

The race for the control of Johannesburg, Tshwane and Nelson Mandela Bay was anybody’s guess. The ANC, DA and EFF all showed confidence that they would win these three metros.

Little did they know that voters had other intentions. By the time the counting of the results was concluded, the fate of these metros had been decided – not by the politicians but by the electorate.

Based on the discussion above, it is clear that the ANC’s outright victory in Buffalo City and Mangaung did not come as a surprise. However, what stunned many observers and the ANC itself was the slightly reduced percentage by which the ANC retained some of these metros. Buffalo City was slightly up at 59.43% compared to the 58.7% obtained in 2016. The 50.63% in Mangaung came as a shock to the ANC. This was despite the fact that the DA did not come anywhere close to the ANC, obtaining less than 20% in Buffalo City and less than 30% in Mangaung.

As expected, the DA secured an outright majority in the city of Cape Town, albeit with a reduced percentage of just over 58%, which was less than what the party obtained in 2016.

This was still better than the 18.63% obtained by the ANC which came second.

The ANC was the biggest loser in this battle for the metros. Although the party obtained the highest votes in eThekwini (42.02%) compared to the DA’s 25.62%, obtained 38.19% in Ekurhuleni compared to the DA’s 28.92% and obtained 33.6% in Johannesburg compared to the DA’s 26.47%, these figures were significantly reduced from what the ANC obtained in 2016.

Regarding the EFF, it continued to show upward mobility as it did in the 2016 local government elections and the 2019 national and provincial government elections. However, this party too was unable to win any of the eight metros it had targeted. It occupied the third spot in seven of them and was pushed to position four in Johannesburg by Herman Mashaba’s new ActionSA.

But why did these three political parties struggle to obtain outright victory in these metros? This is the question which warrants cogent analysis.

First, it was the mushrooming of new political parties. For the very first time, 325 political parties participated in this election. Some of these parties obtained votes but which were not enough to earn them even a seat. Others deprived the three main parties of some votes and were able to get some seats. This reduced the number of votes which would have enabled the big parties to take a metro.

Second, it was the unprecedented increase in the number of people who participated in the local government elections as independent candidates. For the very first time, the number of independent candidates increased exponentially in this election. Like smaller parties, these individuals also took some votes that would have gone to the three big parties. When this happened, the three big parties were unable to get enough votes to allow them to constitute a council on their own. This has paved the way for the formation of “forced” coalitions.

Third, there was voter apathy. Many people did not vote. Some did not register. Others registered but did not show up on the voting day. There were several causal factors. Among them was the fact that councillors have failed to provide basic services to communities.

Another reason is that some people were scared of contracting the coronavirus and thus stayed at home. In certain areas, some of the voters feared for their lives. This was the case in places that were identified as “hot spots” by the security cluster.

Yet another reason is that there were challenges with the voters roll. There are people who registered to vote and showed up at the voting station on the day but were told that their names were not there.

Having five hung metros does not augur well. Service delivery will suffer. Coalitions are not sustainable. The ones that will be formed have been imposed by the election results, they were not planned.

* Bheki Mngomezulu is professor of Political Science and Deputy Dean of Research at the University of the Western Cape.

** The views expressed here are not necessarily those of the DFA.